I45.81

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a condition which affects

repolarization of the heart after a heartbeat. It results in an increased risk

of an irregular heartbeat which can result in palpitations, fainting, drowning,

or sudden death. These episodes can be triggered by exercise or stress.Other

associated symptoms may include hearing loss.

Long QT syndrome may be present at birth or develop later

in life.The inherited form may occur by itself or as part of larger genetic

disorder. Onset later in life may result from certain medications, low blood

potassium, low blood calcium, or heart failure. Medications that are implicated

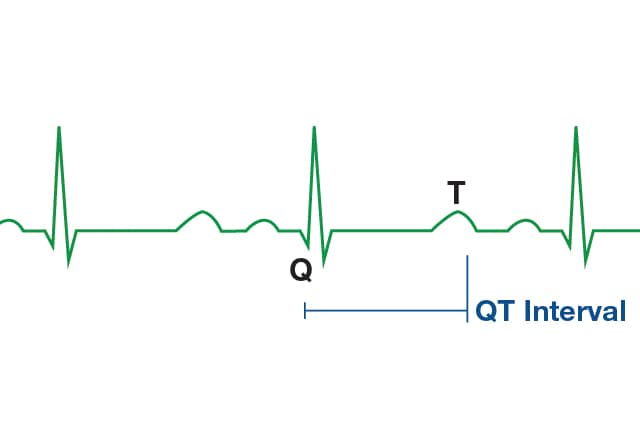

include certain antiarrhythmic, antibiotics, and antipsychotics. Diagnosis is

based on an electrocardiogram (EKG) finding a corrected QT interval of greater

than 440 to 500 milliseconds together with clinical findings.

Overview

Long QT syndrome (LQTS)

is a heart rhythm condition that can potentially cause fast, chaotic

heartbeats. These rapid heartbeats might trigger a sudden fainting spell or

seizure. In some cases, the heart can beat erratically for so long that it

causes sudden death.

Long

QT syndrome is treatable.

In

some cases, treatment for long QT syndrome involves surgery or an implantable

device.

Symptoms

Many people who have long

QT syndrome don't have any signs or symptoms. You might be aware of your

condition only because of:

· Results of an electrocardiogram (ECG)

done for an unrelated reason

· A family history of long QT syndrome

· Genetic testing results

For people who do experience signs and symptoms of long QT syndrome, the most common include:

· Fainting. This is the most common sign of long QT syndrome. Long QT

syndrome-triggered fainting spells (syncope) are caused by the heart

temporarily beating in an erratic way.

· Seizures. If the heart continues to beat erratically, the

brain will eventually not get enough oxygen, which can cause seizures.

· Sudden death. Generally, the heart returns

to its normal rhythm. If this doesn't happen by itself, or if an external

defibrillator isn't used in time to convert the rhythm back to normal, sudden

death will occur.

Inherited long QT syndrome

At least 17 genes

associated with long QT syndrome have been found so far, and hundreds of

mutations within these genes have been identified. Mutations in three of these

genes account for about 75 percent of long QT syndrome cases, while mutations

in the other minor genes contribute a small percent of long QT syndrome cases.

About 20 percent of

people who definitely have congenital long QT syndrome have a negative genetic

test result. On the other hand, among families with genetically established

long QT syndrome, between 10 percent and 37 percent of the relatives with a

positive long QT syndrome genetic test have a normal QT interval.

Doctors have described

two forms of inherited long QT syndrome:

· Romano-Ward

syndrome. This more common form occurs in people who

inherit only a single genetic variant from one parent.

· Jervell

and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. This rare form usually occurs

earlier and is more severe. In this syndrome, children inherit genetic variants

from both parents. They have long QT syndrome and also are born deaf.

Additionally, scientists

have been investigating a possible link between sudden infant death syndrome

(SIDS) and long QT syndrome and have discovered that approximately five to 10

percent of babies affected by SIDS had a genetic defect or mutation for long QT

syndrome.

Acquired long QT syndrome

Acquired long QT syndrome

can be caused by certain medications, electrolyte abnormalities such as low

body potassium (hypokalemia) or medical conditions. More than 100 medications —

many of them common — can lengthen the QT interval in otherwise healthy people

and cause a form of acquired long QT syndrome known as drug-induced long QT

syndrome.

Medications that can

lengthen the QT interval and upset heart rhythm include:

· Certain antibiotics

· Certain antidepressant and antipsychotic

medications

· Some antihistamines

· Diuretics

· Medications used to maintain normal

heart rhythms (antiarrhythmic medications)

· Some anti-nausea medications

Risk

factors

People who may have a

higher risk of inherited or acquired long QT syndrome may include:

· Children, teenagers and young adults

with unexplained fainting, unexplained near drownings or other accidents,

unexplained seizures, or a history of cardiac arrest

· Family members of children, teenagers

and young adults with unexplained fainting, unexplained near drownings or other

accidents, unexplained seizures, or a history of cardiac arrest

· First-degree relatives of people with

known long QT syndrome

· People taking medications known to cause

prolonged QT intervals

· People with low potassium, magnesium or

calcium blood levels — such as those with the eating disorder anorexia nervosa

Inherited long QT

syndrome often goes undiagnosed or is misdiagnosed as a seizure disorder, such

as epilepsy. However, long QT syndrome might be responsible for some otherwise

unexplained deaths in children and young adults. For example, an unexplained

drowning of a young person might be the first clue to inherited long QT

syndrome in a family.

Complications

Most of the time,

prolonged QT intervals in people with long QT syndrome never cause problems.

However, physical or emotional stress might "trip up" a heart that is

sensitive to prolonged QT intervals. This can cause the heart's rhythm to spin

out of control, triggering life-threatening, irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias)

including:

· Torsades de pointes —

'twisting of the points.'

· Ventricular fibrillation.

Short

QT syndrome

Short QT syndrome is a condition that can cause a disruption of the heart's normal rhythm (arrhythmia). In people with this condition, the heart (cardiac) muscle takes less time than usual to recharge between beats. The term "short QT" refers to a specific pattern of heart activity that is detected with an electrocardiogram (EKG), which is a test used to measure the electrical activity of the heart. In people with this condition, the part of the heartbeat known as the QT interval is abnormally short. If untreated, the arrhythmia associated with short QT syndrome can lead to a variety of signs and symptoms, from dizziness and fainting (syncope) to cardiac arrest and sudden death. These signs and symptoms can occur any time from early infancy to old age. This condition may explain some cases of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), which is a major cause of unexplained death in babies younger than 1 year. However, some people with short QT syndrome never experience any health problems associated with the condition.

Causes Mutations in the

KCNH2, KCNJ2, and KCNQ1 genes can cause short QT syndrome. These genes provide

instructions for making channels that transport positively charged atoms (ions)

of potassium out of cells. In cardiac muscle, these ion channels play critical

roles in maintaining the heart's normal rhythm. Mutations in the KCNH2, KCNJ2,

or KCNQ1 gene increase the activity of the channels, which enhances the flow of

potassium ions across the membrane of cardiac muscle cells. This change in ion

transport alters the electrical activity of the heart and can lead to the

abnormal heart rhythms characteristic of short QT syndrome. Some affected individuals

do not have an identified mutation in the KCNH2, KCNJ2, or KCNQ1 gene. Changes

in other genes that have not been identified may cause the disorder in these

cases.

Diagnosis

Short QT syndrome is diagnosed

primarily using an electrocardiogram (ECG), but may also take into account the

clinical history, family history, and possibly genetic testing. Whilst a

diagnostic scoring system has been proposed that incorporate all of these

factors (the Gollob score), it is uncertain whether this score is useful for

diagnosis or risk stratification, and the Gollob score has not been universally

accepted by international consensus guidelines. There continues to be

uncertainty regarding the precise QT interval cutoff that is should be used for

diagnosis.

12-lead ECG (or KOLIBRI)

The mainstay of diagnosis of short QT syndrome is the 12-lead ECG. The

precise QT duration used to diagnose the condition remains controversial with

consensus guidelines giving cutoffs varying from 330 ms, 340 ms or even 360 ms

when other clinical, familial, or genetic factors are present. The QT interval

normally varies with heart rate, but this variation occurs to a lesser extent

in those with short QT syndrome. It is therefore recommended that the QT

interval is assessed at heart rates close to 60 beats per minute. Other

features that may be seen on the ECG in short QT syndrome include tall, peaked

T-waves and PR segment depression.

Published on 23 March 2019